Vectors¶

What is a vector¶

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLkZjai-2Jcxlg-Z1roB0pUwFU-P58tvOx

https://stattrek.com/matrix-algebra/matrix.aspx https://thomas-cokelaer.info/tutorials/sphinx/rest_syntax.html#headings

How do you calculate a vector perpendicular to another?¶

https://www.quora.com/How-do-I-find-a-vector-perpendicular-to-another-vector

In 3D there are many vectors that are perpendicular to a given vector. Just imagine stem of hair brush to be given vector then each hair of the brush is a vector perpendicular to stem-vector. While there are of course infinite vectors perpendicular to any one 3d vector, here is a simple answer to your question. If your vector is (i,j,k) then one possible orthogonal vector is: (j-k, k-i, -i-j)

In 2D if the given vector is (a,b) then vector perpendicular to it is (-b, a). Their dot product is zero.

In three dimensions, there’s a special technique: Suppose you start with a vector (x,y,z).

Take another vector (a,b,c) - any vector will do. Now, consider (yc-zb,az-cx,bx-ay). That vector will be perpendicular to (x,y,z) [and also to (a,b,c)] - I leave proving this to you. In order to get a nonzero vector, just choose an (a,b,c) appropriately.

If you start with a 2-d vector (x,y), pretend you have the vector (x,y,0) and let (a,b,c)=(0,0,1). This will give some other vector (f,g,0), which means a perpendicular vector is (f,g). This gives a special formula: a vector perpendicular to (x,y) is (y,-x) [or (-y,x)].

To get a magnitude of 1, just divide any of those vectors by their magnitude.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCmH4MqbFGs

function [a1cmp] = ortc(a1)

%ORTC Orthogonal complement of column matrix.

%

% [A1CMP] = ORTC(A1) produces an orthogonal complement of a column

% type matrix via QR decomposition.

%

% R. Y. Chiang & M. G. Safonov 7/85

% Copyright 1988-2004 The MathWorks, Inc.

% All Rights Reserved.

% ----------------------------------------------------------------

%

[ra1,ca1] = size(a1);

if ra1 == ca1

a1cmp = zeros(ra1);

else

[u,r] = qr(a1);

a1cmp = u(:,ca1+1:ra1);

end

%

% ----- End of ORTC.M ---- RYC/MGS 7/85 %

https://www.ece.rutgers.edu/~orfanidi/ece525/svd.pdf

There are many ways to construct the orthonormal basis U starting with B. One is through the SVD implemented into the function orth. Another is through the QRfactorization, which is equivalent to the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization process. The two alternatives are:

Inner and outter products¶

It might be most helpful to see this using basic finite-dimensional matrix and vector calculations. I’m not sure how familiar you are with this.

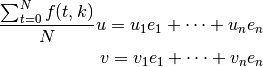

For simplicity, pick two vectors u, v in mathbb{R}^n. If we pick the standard basis e_1, ldots, e_n, then u and v looks like

(of course you know that  ,

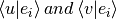

,  are extractable via the projections

are extractable via the projections  ).

).

Now, ![\left<u|v\right> = u \cdot v = u_1 v_1 + \cdots + u_n v_n = \left[\begin{array}{ccc}u_1 & \cdots & u_n\end{array}\right] \cdot \left[\begin{array}{c}v_1 \\ \vdots \\ v_n\end{array}\right]](_images/math/9b0b2ba714ad158ffb75b0a217abf97de780113e.png)

with the last equality coming from the orthonormality of the basis vectors. If we think of u, v as actually being column vectors, then we can write

since the row vector  is the transpose of the column

is the transpose of the column  . The matrix multiplication is of a 1 times n array with an n times 1 array, resulting in a 1 times 1 array, or just a number. In bra-ket notation, transposing the column to the row turns the ket left|uright> into the bra left< u right|.

. The matrix multiplication is of a 1 times n array with an n times 1 array, resulting in a 1 times 1 array, or just a number. In bra-ket notation, transposing the column to the row turns the ket left|uright> into the bra left< u right|.

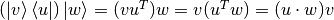

So much for the inner product. But notice that the matrix multiplication rules still work if we multiply the column by the row, in the opposite order. In that case, we don’t get a single number like in the first calculation - in fact, we get an n times n matrix. We get:

![v u^T = \left[\begin{array}{c}v_1 \\ \vdots \\ v_n\end{array}\right] \cdot \left[\begin{array}{ccc}u_1 & \cdots & u_n\end{array}\right] = \left[\begin{array}{ccc} u_1v_1 & \cdots & u_n v_1 \\ \vdots & & \vdots \\ u_1v_n & \cdots & u_n v_n\end{array}\right] = \left|v\right>\left<u\right|](_images/math/d1c4d2d895e723f9fd9d0cb3b2b90dc8f41fcf47.png)

Now this is an operator that can act on other vectors. In fact, if  is any other vector, then notice that when we evaluate this matrix on

is any other vector, then notice that when we evaluate this matrix on  , it is actually equal to

, it is actually equal to  where the last equality comes from noticing, like before, that

where the last equality comes from noticing, like before, that  is just the inner product of

is just the inner product of  and

and  .

.

So here is a way to create an operator from two vectors. It’s called their ‘outer’ product, because it’s the opposite of an inner product!

When you have states in quantum mechanics, the vector space is no longer just  . The vector-and-matrix analogy no longer works because there is no longer a finite basis (in general). But the algebra remains the same. You can think of the bras as being row vectors and the kets as being column vectors. Row times column results in a scalar, ‘inner’ product (bra-ket), and column times row results in a matrix, ‘outer’ product (ket-bra).

. The vector-and-matrix analogy no longer works because there is no longer a finite basis (in general). But the algebra remains the same. You can think of the bras as being row vectors and the kets as being column vectors. Row times column results in a scalar, ‘inner’ product (bra-ket), and column times row results in a matrix, ‘outer’ product (ket-bra).

The inner product creates a scalar and the outer a skew-symmetric matrix. If you sum like-terms of this matrix you get a vector which also results from the cross product computation.

Contrast with Euclidean inner product https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Outer_product If m = n, then one can take the matrix product the other way, yielding a scalar (or 1 × 1 matrix):

{displaystyle leftlangle mathbf {u} ,mathbf {v} rightrangle =mathbf {u} ^{textsf {T}}mathbf {v} }{displaystyle leftlangle mathbf {u} ,mathbf {v} rightrangle =mathbf {u} ^{textsf {T}}mathbf {v} }

which is the standard inner product for Euclidean vector spaces,[4] better known as the dot product. The inner product is the trace of the outer product.[6] Unlike the inner product, the outer product is not commutative.

Multiplication of a vector {displaystyle mathbf {w} }mathbf {w} by the matrix {displaystyle mathbf {u} otimes mathbf {v} }{displaystyle mathbf {u} otimes mathbf {v} } can be written in terms of the inner product, using the relation {displaystyle left(mathbf {u} otimes mathbf {v} right)mathbf {w} =mathbf {u} leftlangle mathbf {v} ,mathbf {w} rightrangle }{displaystyle left(mathbf {u} otimes mathbf {v} right)mathbf {w} =mathbf {u} leftlangle mathbf {v} ,mathbf {w} rightrangle }.

https://www.intmath.com/trigonometric-functions/2-sin-cos-tan-csc-sec-cot.php